“Why, land is the only thing in the world worth workin' for, worth fightin' for, worth dyin' for, because it's the only thing that lasts.”

Can you hear those words, offered in an Irish brogue, and not feel them resonate deep in you? You don’t have to be Irish, or of Irish descent, to feel the impact of their meaning. For centuries Americans have chased the dream of owning their own piece of land, from the first colonials leaving Europe, hoping for the opportunity to own something and live on their own terms, to the newly arrived immigrants of the nineteenth and twentieth century, following the beacon of land in the West advertised across a war-torn Europe. You don’t need to be a farm kid to understand the importance land has played in the making of America.

This centrality of land to the American experience offers a unique opportunity for genealogists and family historians hoping to uncover their family’s past. Land deeds, wills, estate settlements, and yes mortgages, sheriff sales, and loans can shed light on our ancestors’ lives and even track family members with common surnames. There were two George Toothman’s in our family tree who descended from related but different fathers. Which one was our direct ancestor? The one who inherited a particular tract of land that was then later sold with a release signed by the known wife of “our” George. Recreating neighborhoods based on deeds provides a great list of neighbors who were likely close to your ancestors and played significant roles in their lives. When did your ancestor head west? Probably about the time he sold his land in West Virginia. There are numerous instances where land can provide answers to your genealogical questions.

An 1858 neighborhood recreated using deeds and plotting in DeedMapper.

For those of us who grew up as farm kids, the land itself becomes part of our family, not just an address or point on a map, but a living breathing piece of us. The emotions connected to her might not be of only happy times but the harder emotions of sadness, anger, or fear, which makes our connection all the deeper. I will never forget the day that my father and I renozzled a pivot when the corn was already over my head. I have never been so hot in my life. Or the hours spent scaling the Little Blue creek banks cutting musk thistle, battling mosquitoes, nettles, and my brother. If you grew up farming, or on a particular piece of land, you inevitably wonder about those who came before you to that piece of heaven or hell. Whether they were related to you or not, there is a connection you share through the land.

There is a depression in a pasture where I grew up, and the story was always that it was a dug out, left by the person who homesteaded that tract. Who was he though? When I started writing the biography of this land I discovered the homesteaders, George and Richard Spicknall, and was able to download their homestead packets. A little online search and I found a picture of him in his Union Army uniform. All of a sudden, that slight depression had a face to go with it, and a story.

Richard S. Spicknall

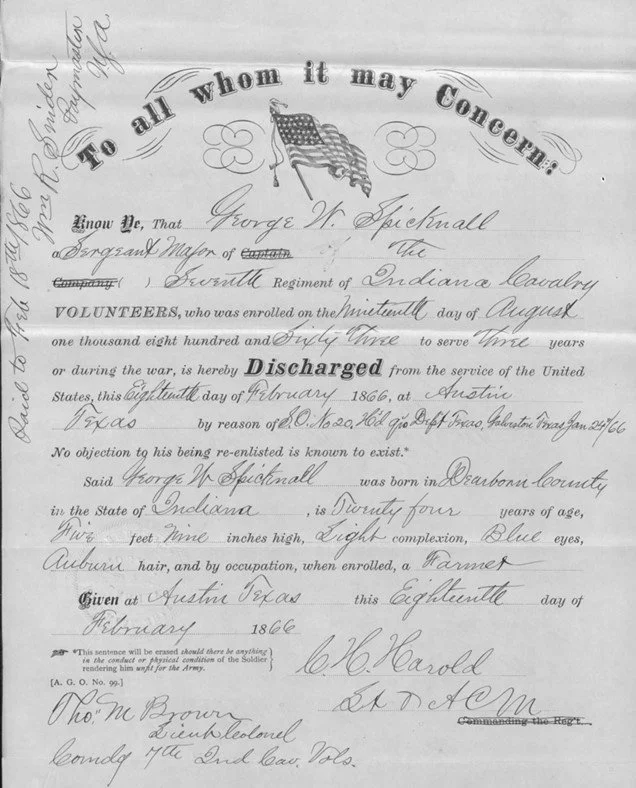

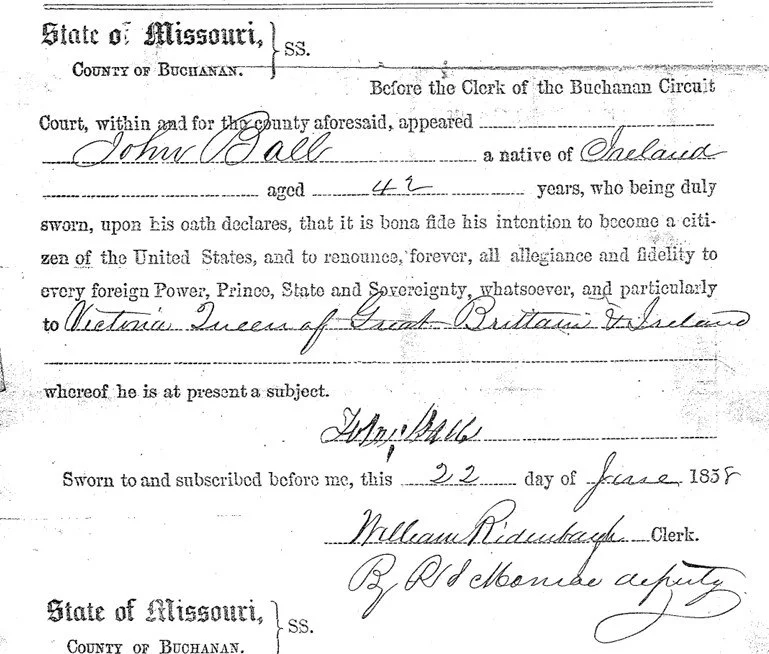

Never skip over a homestead packet. These are often gold mines, not necessarily genealogical data, but information about your ancestor’s life. It will describe the house the individual lived in (and how many family members resided there as well). Some 20th century homesteads will give the acreage planted each year and the yields – or a lack of yield. If your ancestor was an immigrant his or her nationalization paperwork may also be included in the file. If the individual was a soldier in the Civil War he may have included discharge papers in the homestead application.

George Spicknall’s discharge papers, included in his homestead file.

John Ball filed to become a citizen of the United States when he applied for a homestead in 1858.

In addition to the population censuses agricultural censuses were conducted on a ten year time frame. The individual returns for the agricultural censuses of the 19th century provide a look at the individual’s farm production for the year prior. The availability of these individual returns vary based on location and year. But if your ancestor was a farmer it is worthwhile looking up the agricultural census for his or her area. I found it interesting that my Irish immigrant ancestor planted a full 1.5 acres LESS of Irish potatoes in 1879 than his neighbors. Perhaps he was sick of potatoes? In addition to these censuses look at county history books, they often mention major weather or pestilence that affected the area. My ancestor was a newly arrived homesteader when the grasshoppers came through the county and ate everything, “including the broom handles.”

You may be lucky enough to have diary entries or letters from family members describing the land or events that took place there. We always thought that the mounds along the creek were ancient burial grounds, but you never know. But then a story left by my great-great-aunt gave more credence to this hypothesis. As a young girl she wrote about the Native Americans who would ride up to their farmhouse along this creek. They had come to visit their burial grounds.

“[Native Americans] came through these parts in early spring months. They were

checking the graves of their buried chiefs along the Little Blue River.

One hot spring morning my father Emet his brother-in-laws and my

grandfather Ed Denton were loading fat hogs into a lumber wagon for market.

One hog became overheated and died. They took it from the wagon and laid it in

the farmyard. Just then Two [Native American] Scouts came into yard rode in the yard for

water for to water their mounts. They asked Grandpa Ed, if they might could

have the hog. He motioned for them to take it. – They signalled to other Scouts

in the road. So several of them came running across the yard with waving long

knives in their hands. –My Mother (Effie) saw them this from the kitchen

window. She nearly fainted, thought they were going to scalp the men. She

didn’t understand the situation. This of course was two and ½ years before my I

was born arrival. I’ve heard my families tell it many times. –I always thought

t’would be fun to dig into some of these mounds in our timber where these [Native American]

chiefs & their treasures were buried. sitting upright on their horses in mounds But

somehow the years slipped by and I never got it done. All of their treasures were

suppposed to have been be buried with them.”

If you want to track the ownership of land, or your ancestor’s location in a particular county, it has become much easier to do this from your home computer. Besides the Catalog on Family Search, many county government websites now have online access to old deeds. This makes searching for the records of your ancestors much, much faster. If you are not able to find a link to these old deeds on your county website, email the register of deeds. If you contact them with specific information (a land description or a certain name and date) I have found them incredibly very happy to help!

Check the Catalog at Family Search for your county. Deeds are listed under Land and Property.

Wetzel County, West Virginia has deeds available for look up under public records.