SLAVERY IS DISCUSSED IN THE FOLLOWING POST. THE VIEWS AND LANGUAGE USED IN HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS IS PRESERVED AND MAY BE TRIGGERING. IT DOES NOT REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THIS AUTHOR.

I do not have any African American heritage in my family tree. Or, at least, nothing that shows up in documentary or DNA evidence. Most of my family migrated through the US via a northerly route, so I haven’t had a lot of experience researching Southern plantations. My skills in African American research, therefore, are minimal. In the past few years alone, however, the resources for researching these ancestors have increased dramatically, a very exciting advancement. If you do have African American Ancestors in your family tree, I highly recommend the following resources:

DNA testing – this is a great tool that shouldn’t be overlooked if you wish to discover where your ancestors may have originated, or family members that you don’t know about.

Rootstech by Family Search has a large library of videos on a variety of topics. Search African American and you will see a list of great videos to help you in your research. https://www.familysearch.org/en/rootstech/search?f.language=en-US&f.text=African%20American&p.index=0

Family Locket Podcast has a great series of episodes about African American research. https://familylocket.com/the-research-like-a-pro-genealogy-podcast/

Slave Narratives Collection at the Library of Congress – this collection includes over 2,300 first person narratives of former slaves collected 1936-1938. While you are unlikely to find your ancestor directly quoted in them, they offer a glimpse into what your previously enslaved ancestor experienced. They are arranged by state, then by last name and available online. https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writers-project-1936-to-1938/about-this-collection/

Family Search Wiki – always a great place to check for all subjects and locations!

Southern Claims Commission https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Southern_Claims_Commission

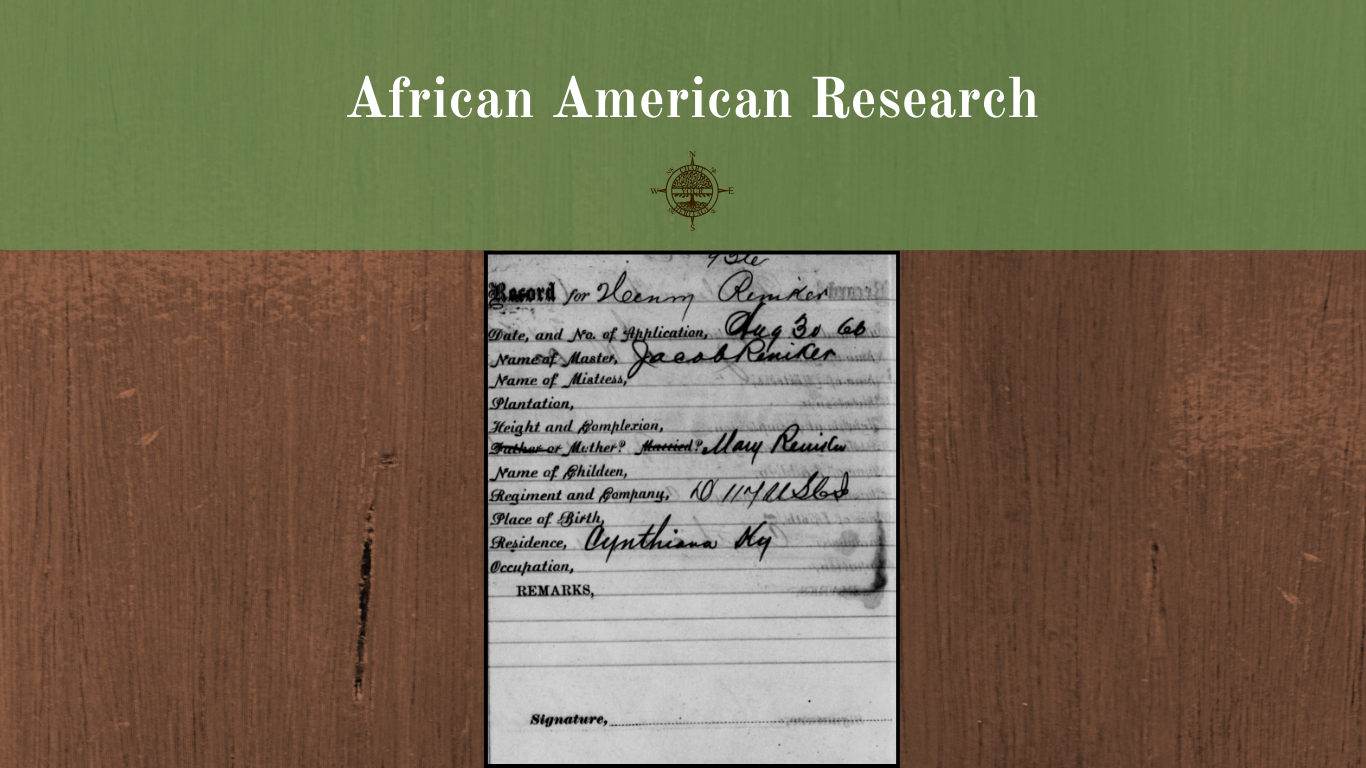

United States, Freedman's Bank Records - FamilySearch Historical Records https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States,_Freedman's_Bank_Records_-_FamilySearch_Historical_Records

African American Genealogy https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/African_American_Genealogy

Any lecture or webinar by Dr. Deborah A. Abbott, PhD!

While I may not have experience researching African American ancestry, I will comment on the use of probate documents for those who are researching formerly enslaved individuals. And, for those who would like to learn about our country’s history.

I am a fan of a good probate. Probates can provide an amazing window into an ancestor’s life – were they affluent, what land did they own, the name of their wife, children, and grandchildren even. Often there are supplemental records to the probate: court cases brought by the widow or children disputing some partition of land, unpaid bills left to the heirs, or family disputes. It is almost like the historical version of reality television. If you are lucky and the deceased left a will, the probate will include it along with appraisements, sales, and distribution of property.

I have gone through some southern wills in the course of various research, and they provide an important glimpse of our country’s past. The truth of slavery is impossible to avoid while reading these, a truth that is important for us all to remember.

The last will and testament of Augustus H. Anderson of Burke County, Georgia, 1852 excerpts:

“I lend to my wife Sarah During her natural life my negro slaves, Chloe, Mingo, Laura, Virginia Patience, Old Adam and any other two she may select…”

“To my old slav[e] – Adam (lent to my wife) and Maria I give the sum of twenty dollars during their lives each annually to be paid to them by my executors, and I request that said slaves be kindly treated and provided for, and not put to any hard work.”

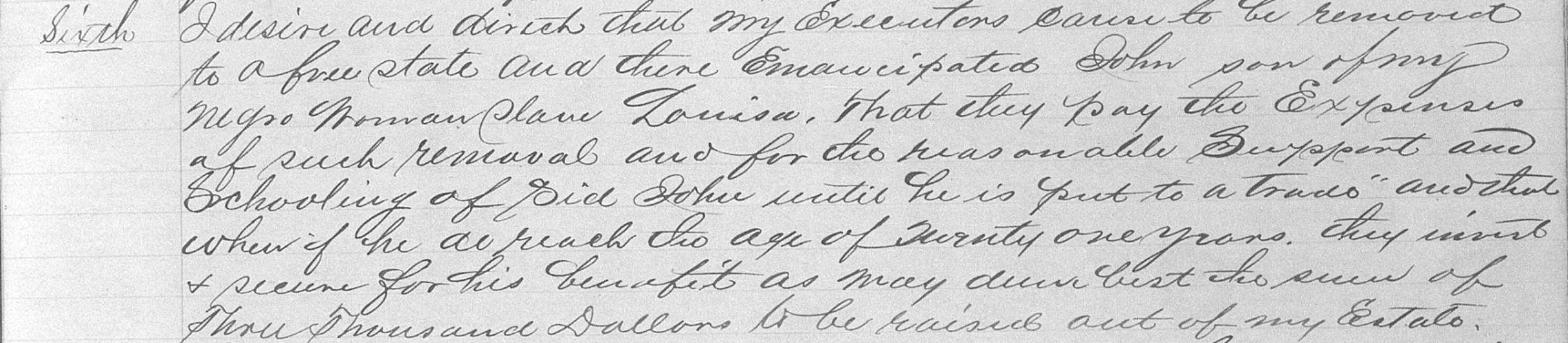

“I desire and direct that my executors cause to be removed to a free state and there emancipated John son of my negro woman slave Louisa. That they pay the expenses of such removal and for the reasonable support and schooling of s[a]id John until he is put to a trade and that when if he do reach the age of twenty one years, they invest and secure for his benefit as may deem best the sum of three thousand dollars to be raised out of my estate.”

Excerpt from Augustus H. Anderson of Burke County, Georgia Will, dated 1852.

“I desire and direct that my negro slave Louisa mother of said John shall be kept at my Burke plantation till the 1st January 1875. That she be kindly treated and provided for. That she be employed as a seamstress as hereto fore and that she be paid by my executors and till that time the sum of fifty dollars. If she chose then in 1875 to go to a free state and be emancipated my Executors are directed to carry out her determination And to invest and secure for her use as they may think best the sum of two thousand dollars to be raised out of my estate…”

Reading this will brings one to think that there may have been a greater connection between Augustus Anderson and the slave known as John. If John had descendants this will would be particularly valuable to them, indicating John’s origins in Georgia and even his mother’s name, Louisa. I do not know what became of Louisa or her son John.

A common phrase found in probate records of slave holders, and other documents, is “natural increase.” When a slave holder left a particular female slave to a relative, or sold a slave, the legal jargon would include: “and her natural increase.” This ensured that the children of the said slave were also accounted for in the disposal of the property. I have found these probates difficult to transcribe, but all the more important for that.

The last will and testament of John Pendergrass of Jackson County, Georgia, 1859 excerpts:

“I give and bequeath to the sale and separate use of my grand daughter Sarah Coleman a Negro girl named Laura, for and during her natural life free from the control, contracts and liabilities of any future husband of said Sarah Coleman, and after her death it is my will and wish that said Negro Laura and her increase if any, shall equally divided between the children of my said grand daughter Sarah, and if she should die without children or the representative of children, then the said Negro and increase is to revert to the brothers and sisters of said Sarah.”

Excerpt from John Pendergrass of Jackson County, Georgia Will, dated 1859.